A Cautionary tale of the Sixties

by John Stark Bellamy II

Author’s note: Some of the names, most especially that of the central character of this narrative, have been altered, sometimes to protect the innocent and sometimes to shield the guilty.

My brothers and I flirted with catastrophe many times during the drug-drenched days of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Surely, however, we never came closer to disaster than the Joe Rupple Christmas imbroglio of 1967. At the time I was so shocked and scared I could scarcely believe the events that were occurring in front of me. But it did happen, and it came about in this wise.

I arrived home for Christmas from my first semester at St. John’s College on December 22. The following day my brother and I passed the tedious hours in the desultory but prolonged grass smoking that had become de rigeur for the last year on the third floor of the family manse. My mother had already informed us that my younger brother was bringing a guest, Joe Rupple, home for the holidays from the eastern college both attended, as Joe’s parents lived in Singapore and it would be inconvenient for him to fly back there simply for Christmas. So that evening my elder brother and I motored to the Greyhound Bus Terminal at East 13th Street and Chester Avenue to pick up my younger brother and Joe. Higher than kites but with unencumbered hearts, we were not prepared for what broke loose when we got there.

I arrived home for Christmas from my first semester at St. John’s College on December 22. The following day my brother and I passed the tedious hours in the desultory but prolonged grass smoking that had become de rigeur for the last year on the third floor of the family manse. My mother had already informed us that my younger brother was bringing a guest, Joe Rupple, home for the holidays from the eastern college both attended, as Joe’s parents lived in Singapore and it would be inconvenient for him to fly back there simply for Christmas. So that evening my elder brother and I motored to the Greyhound Bus Terminal at East 13th Street and Chester Avenue to pick up my younger brother and Joe. Higher than kites but with unencumbered hearts, we were not prepared for what broke loose when we got there.Joe and my younger brother were the first passengers off the bus, and the four of us huddled by its dirty side, waiting while the luggage was unloaded. I had noticed my younger brother looking nervous when he stepped off the bus, and I quickly discovered why. He had just endured eighteen hours on a Greyhound bus with Joe Rupple, and it was immediately obvious to me what he had known every second of that long journey: Joe Rupple was high—higher than just about anyone we had ever seen.

It wasn’t his dress or grooming that drew attention. Joe was handsome enough in a rangy way, and his full beard gave him an Old Testamenty gravitas that added several years to his actual age of 18. But it took only one look at his face to see that something was terribly wrong. His eyes, hugely dilated, gleamed back at you with the unmistakable shimmer of drug-fueled lunacy. But that wasn’t the worst part. Scarier still was his voice: an overpowering verbal Niagara of high-pitched, semi-hysterical and non-stop speed-freak words, words and more words.

What he was saying was alarming enough; what was worse was that he was saying it right OUT LOUD in a tone which could be heard a block away. Nor did he wait for a response to any of the words that poured from his mouth in an incessant flow: “YOU MUST BE THE BROTHERS! I’M JOE! ARE YOU STONED? DO YOU WANT TO GET STONED? LET’S GO TO THE LAVATORY AND GET HIGH? JOHN! JOHN! JOHN! LET’S GET HIGH IN THE LAVATORY! DO YOU HAVE THE HASH? IS THE PIPE STILL IN YOUR BOOT?! LET’S GET HIGH! LET’S GO TO YOUR HOUSE TO THE THIRD FLOOR AND GET REALLY, REALLY STONED!” Hoping to interrupt this incriminating monologue, I pushed him away from the bus and took him to the Men’s Room. That was a mistake. Seconds later, I dragged him out, just after he had invited a young black man attending a call of nature there to “smoke some dope with us soul brothers, dig, man?”

Grabbing the luggage, we finally managed to hustle Joe into the car and sped homeward. As the miles slipped by, Joe continued his non-stop monologue, alternately gushing at how glad he was to be with those hip Bellamy boys and petulantly demanding that we smoke some dope in the car.

Once we got home, things unexpectedly cooled down. Joe sat down to a late dinner with us and aside from some inappropriate boisterousness and embarrassing candor, managed to get through the meal without unduly alerting the suspicions of my parents. For one thing, whatever his behavior to the wary eye, he didn’t mention drugs and for another, my parents had already been prompted to make allowances for his behavior by his mother’s telephoned warning that he’d lived abroad for most of his life and was a relative stranger to American customs and behavior. As soon as the meal was finished, we hustled him to the third floor and smoked opiated hashish until we passed out.

Well, not quite all of us. When we woke up the next morning we discovered that Joe had not slept, nor had he been still. During their months together at college my younger brother had regaled him with tales of our adolescent mischief, and Joe had naively but indelibly incorporated elements of these anecdotes and their embedded personalities into his intense fantasy life. He was particularly fearful of a mythical figure known simply as “Scott” (a local high-school teacher notorious for smoking dope with his students), more positively keen to meet a legendary hipster known as “Slim” (a high-school chum of legendary muscularity and capacity for ingesting drugs) and childishly anxious to impress all he met with testimonials as to his personal sophistication and experience, particularly with reference to drug consumption. So while we had slept that night, he had methodically worked his way through the bookcases of my adjoining room, frantically scribbling such totemic words as “Scott,” “Slim” and his absolute favorite, “Reality” in my books and, when periodically inspired by thoughts of the impending holiday, “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Bag!” He had also, although this did not become apparent for some days, purloined Christmas ornaments from the first floor Christmas tree and concealed them in various unexpected places, mostly under chair cushions and at the back of bookcases.

Breakfast on Christmas Eve morn was a nightmare. Joe babbled incessantly and repetitively as we ate, and I could see my mother showing the first signs of real concern, the corners of her mouth drawing tighter and tighter as the dimensions of his mania progressed. Indeed, the mood at the table became so uncomfortable that we were relieved when Joe abruptly arose from his seat and disappeared.

The winter afternoon hours slipped by with no sign of Joe. It being Christmas Eve, my parents had prepared their annual holiday dinner, an elaborate entertainment to which they inflexibly invited several dozen of their oldest and dearest friends. Five o’clock came, darkness descended and the first guests began straggling in—and still no sign of Joe. By 6 pm the party was in full swing, the alcohol was briskly flowering and still no sign of Joe. Uninterested in the party, my brothers retreated to the third floor lair for some serious hashish consumption, leaving me to greet the guests as they arrived at the front door and subsequently assuring that they were well supplied with glasses of champagne.

I knew something was amiss when the door bell rang, and I opened the front door to find no one there. This likely meant there was someone at the back door, so I walked there, opened the door . . . and found myself looking at an unexpected threesome: a terrified Joe Rupple in the obvious custody of two burly Cleveland Heights policemen.

The story as best the policemen could reconstruct it went like this. After leaving the house that morning, Joe had eventually wandered into nearby Lake View Cemetery, about which he had likewise heard many intriguing tales from my younger brother. He’d spent the afternoon walking around the cemetery and, he later claimed, actually encountered my uncle’s gravestone, an unsettling event, as it was graven with my name: JOHN STARK BELLAMY. Eventually, he wandered out of the cemetery, lost and disoriented, and began walking down Mayfield Road. We’ll never know what was going on in his chemically addled head, but whatever it was moved him to cross the street and start knocking on the doors of the homes there. Then, as soon as someone answered the door, he would scream maniacally, “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Bag!” and run away. Eventually, someone called the police, they picked him up, and he had just enough brain cells left to tell them with whom he was staying.

It could have been much worse. The two cops probably—hell, certainly knew Joe was higher than a kite, and they could easily have made things highly unpleasant for both him and us. But, thanks to my father’s prominent position as a journalist and the known fact that we were well acquainted with our back-fence neighbor—the Police Chief of Cleveland Heights—they decided to handle the matter with, ah, considerate discretion. I was soon joined in this back door colloquy by my father, to whom they explained that Joe had been acting in an irrational manner and had frightened some residents, and they were more than happy to relinquish Joe to my father’s custody and leave the matter to his discretion.

I don’t know what we should have done. I can only be sure about what we did, which was to hustle Joe back up to the third floor and ply him with more narcotics, in the hope that that enough narcotics would conk him out and, perhaps with the aid of a good night’s sleep, calm him down at last.

It didn’t work. The first thing that struck me as I struggled awake the next morning was that Joe was already up and bustling around the third floor. Indeed, when I reached full consciousness I realized he had already busied himself by disassembling the flushing mechanism of the toilet tank and was now attempting to reconstruct it as a serviceable hash pipe, an obscure craft that he and my brother had learned at college. But I barely noticed this minor incident and the disagreeable misfortune that we now lacked a working third-floor toilet—for I was immediately distracted by the fact that Joe Rupple was talking faster than anyone I had ever heard in my life. Sure, I’d experimented with some amphetamine pills and the acid we frequently dropped was heavily laced with the stuff—but Joe’s current logorrhea was clearly pathological and downright scary. We all took turns trying to talk him down but with little success, so we decided we had to get him out of the house before his symptoms became obvious even to non-drug users like my parents.

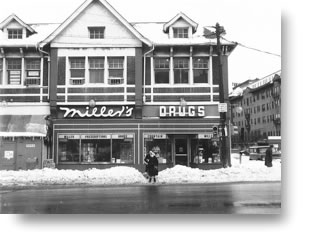

My recollection is that we walked two blocks over to Miller’s Drug Store at Cedar-Fairmount and sat at the counter for an hour, drinking cherry cokes and eating order upon order of heavily buttered toast. The food and the outdoor air seemed to have the hoped for sedative effect on Joe—that is, until we got home. The moment we came through the back door he started running up the stairs to the third floor. Hot on his heels, we followed.

My recollection is that we walked two blocks over to Miller’s Drug Store at Cedar-Fairmount and sat at the counter for an hour, drinking cherry cokes and eating order upon order of heavily buttered toast. The food and the outdoor air seemed to have the hoped for sedative effect on Joe—that is, until we got home. The moment we came through the back door he started running up the stairs to the third floor. Hot on his heels, we followed.We needn’t have hurried, for there was no sign of Joe when we got to the third floor. But a minute later my mother shouted up the stairs that Joe was standing outside her window—on the second floor roof of the house. We ran down to her bedroom and, sure enough, there was Joe, gesticulating wildly and shouting from the other side of the window. There was only one explanation, and it was evident even to my mother: he had crawled out the third floor window at the front of the house and leaped down to the second floor roof.

Matters degenerated rapidly after that. By now it was impossible to conceal his condition from anyone. Ceaselessly pacing, Joe couldn’t stop talking, and his speech was a high-pitched, unstoppable monologue of catch phrases and repetitive slang welling up from his addled brain. “Fish? Reality! Slim?” and constant references to the feared “Scott!” Not to mention his repeated admonitions to “Have a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Bag!”

My mother may have been naďve about drugs, and she had long since become used to young men outrageously acting out in her presence. But she wasn’t an idiot, and it was obvious that Joe had reached the point where he was dangerous to himself and possibly others. So she contacted the only mental health professional she knew, the husband of my father’s first-cousin, a psychologist whom, for purpose of this memoir we shall call “Dr. Scabman.”

An hour or so later, Dr. Scabman got to the house. To say the least, both his odd appearance and disquieting manner only increased Joe’s agitation and paranoia. Repeatedly shouting at him, “Are you Scott? You’re Scott—aren’t you?” Joe refused to answer the doctor’s queries about his condition and waxed wilder and more menacing by the minute. Fortunately, at this juncture, our friend Wilbur arrived.

Like most of our friends in that era, Wilbur was a little, well, eccentric. For example, he was one of the few teenagers I knew who wrote properly scanning sonnets. Bohemian almost to a fault—a category in which he had much peer competition--Wilbur boasted an interest in the farther reaches of English literature, charmingly affected manners, a taste for the occult and dandyish dress. In other words, he was just the weirdly calming and slightly bizarre influence needed under the circumstances. Impressed by his unusual manner and fanciful dress, Joe soon concluded that Wilbur was a magician with great powers and special knowledge. While they chatted, Dr. Scabman consulted with my mother. To say the least she was in a difficult position. With Joe’s parents in Singapore, happily ignorant of his dire condition, she was in loco parentis, confronted with a novel situation and unsure what to do. But finally, after some consultation with my father by telephone, it was decided to take Joe down to Hanna Pavilion (the psychiatric component of University Hospitals) for diagnosis and possible hospitalization. With Wilbur by now astutely playing the role of his magical mentor and spiritual director, Joe was eventually coaxed into an automobile and I accompanied him, Wilbur, my mother and Dr. Scabman to Hanna Pavilion.

There, the nightmare continued. Directed to the 4th floor, we soon found ourselves uneasily ensconced with Joe in a locked ward—with at least a dozen other mental patients, some staff and what I recall was a policeman standing guard. Things got off to a shaky start with Joe turning to me, and in the presence of the guard, asking, “John, why don’t you get that hash and pipe out of your boot and we’ll toke up with this fine policeman?” Notwithstanding the fact that I did have half an ounce of hashish on my person—with events breaking fast and furious it hadn’t seemed safe to leave it anywhere in the house—I coolly replied that I was furnished with no such materials and that his hope was vain. Every few minutes Joe would be shuttled out of the room by doctors for further examination, then returned, while we waited and the hours slipped by. At last, I think it was about 5 p.m.—perhaps five hours after this crisis had developed—word finally came that Joe could not be admitted to Hanna Pavilion. So once again, Wilbur and I bundled him into the car and our strange entourage motored a few blocks over to Mt. Sinai Hospital on East 105th Street. Whisked quietly upstairs to the psych ward, Joe was quickly signed in and left the room in the custody of two men in the proverbial white coats. Somberly, my mother, Dr. Scabman, Wilbur and I began walking to the elevator. But just as the doors opened, we heard a terrible scream behind us and wheeled around to see Joe running towards us, screaming “Don’t leave me! Don’t leave me! Don’t leave me!” as a phalanx of white-coated men chased after him. Catching him as he cowered before us, they pinioned his arms and dragged him away, screaming and fighting every painful, anguished step of the way.

The incidents of the subsequent two months lacked the exciting drama of Joe’s early days but provided plenty of prolonged and unpleasant tension. A week after Joe’s incarceration, his mother arrived to take up temporary residence at my parents’ home while she dealt with her hospitalized son. She was not, to say the least, in a good mood, notwithstanding her gratitude to my mother for her initial handling of a difficult situation. Utterly convinced of her son’s rectitude, she refused to believe that his previous over-experimentation with drugs, well attested to later by various college acquaintances, had inevitably led him to the chemically-induced psychosis that now possessed him. (Even my younger brother didn’t know the genesis of his breakdown—he only knew that Joe had gone to Boston with several hundred dollars and returned from there in a drug-demented state, just hours before his projected jaunt to Cleveland.) Unable to learn exactly what had triggered his descent into madness—the only coherent clue she wrung out of Joe was the feeble admission that he might have taken a solitary “pep pill” to help him study for his semester finals—his mother began selecting scapegoats for her son’s pathetic condition.

She didn’t have far to look and her residence at the Bellamy house made her quest all too easy. Immediately and instinctively focusing on my younger brother—who returned her disdain with relish—she made it her mission to discover and expose, if possible, my brother and the rest of us in possession or use of the kind of drugs she suspected had caused the disintegration of her son’s mind. Restlessly stalking the corridors and rooms of the house, she would suddenly pounce upon us, peering into our ranks and ransacking our rooms in hopes of espying a telltale corncob pipe, a plastic marijuana baggie or an incriminating chuck of hashish. She never succeeded in her researches but there were several close calls—we weren’t about to stop using drugs daily just because of some nosy parent—and it was nerve-wracking having our own personal Javert lurking about at all times and in unexpected places. But in early January my younger brother escaped her scrutiny by going off to New York City to fulfill his off-campus commitment and I departed soon after, returning to Annapolis for my second semester at St. John’s College. Mrs. Rupple remained at my mother’s house for several months more, finally returning with Joe to Singapore in the late spring of 1968.

That was pretty much the end of the Joe Rupple episode. As a token of her gratitude, Mrs. Rupple purchased a badly needed dryer for my mother’s basement and she kept in touch by Christmas card for some years after that. Joe never returned to my brother’s college and the last I heard of him was that, after years of drug abuse and repeated personal crises that nearly bankrupted his parents, he had eventually settled down to some success as a professional chef in New Orleans. I don’t know whether that is so but I do now that he made Christmas 1967 a Yuletide to remember.

Read the upcoming installment of Cleveland Confidential next week in CoolCleveland.com.

Read earlier episodes of Cleveland Confidential here.

--***--

Photo credits: 1) Greyhound Bus Terminal; 2) Heights Center Building, 12429 Cedar Road on 2/11/71. Includes Miller's drug store. Alcazar Hotel can be seen on the far right. Photo courtesy of Cleveland Heights Historical Center.

Former Clevelander John Stark Bellamy II is most notorious for his books chronicling Cleveland murders and disasters, such titles as They Died Crawling, The Maniac in the Bushes and Women Behaving Badly. Countryman Press has also published an anthology of his Vermont murder tales, Vintage Vermont Villainies. This CoolCleveland.com exclusive is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progess, Wasted on the Young.

Former Clevelander John Stark Bellamy II is most notorious for his books chronicling Cleveland murders and disasters, such titles as They Died Crawling, The Maniac in the Bushes and Women Behaving Badly. Countryman Press has also published an anthology of his Vermont murder tales, Vintage Vermont Villainies. This CoolCleveland.com exclusive is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progess, Wasted on the Young.This fall Gray & Co. will publish a compilation of his disaster stories, including narratives of the Cleveland Clinic gas tragedy, the East Ohio Gas Co. explosion, the 1916 waterworks tunnel blast and a dozen more defining Cleveland castrophes.

Although he keeps a fond and constant eye on all things Cleveland cool and otherwise, John now lives with his wife Laura and their dog Clio in the most soothing part of Vermont, where he continues to recuperate from the excitements and follies of his excessively prolonged youth.