The Tim Buckley Story

by John Stark Bellamy II

Forty years on, I can’t recall precisely whether it was the summer of 1967 or 1968, although the compulsive gravity of nostalgia inclines me to believe it was the former, the storied and drug-fogged “Summer of Love.” But I do remember what happened and how. It was one of my rare life encounters with a bona fide celebrity, and it’s only justice to admit that it probably brought of the worst in both of us.

It was a sultry Saturday night in August, suffocated with humidity and the stale anger of teenaged boredom. Two nights before, I, my brother Christopher and a few friends had hied ourselves down to University Circle to see Tim Buckley perform at “La Cave,” then Cleveland’s sole performing venue for what we smugly termed “progressive” or “underground” pop music. Anxious to be seated close to the stage, we stood in a line on the stairs for two hours before the doors opened. We needn’t have--for it happened that we were the only ones who show up for the night’s performance. The La Cave manager, Stanley Kain, a hard-headed entrepreneur, promptly cancelled the performance and declined, as was his wont, to furnish any refunds. But he generously allowed us to stay as Buckley and his two-man band performed a brief rehearsal, the highlight of which was a languorously slow and hitherto unrecorded version of the Supremes’ hit, You Keep Me Hangin’ On. It made us feel special to be his select audience but the music ended all too quickly, and we quickly found ourselves back on the street with a tantalizingly brief memory and no remaining funds for any of Tim’s subsequent performances.

It was a sultry Saturday night in August, suffocated with humidity and the stale anger of teenaged boredom. Two nights before, I, my brother Christopher and a few friends had hied ourselves down to University Circle to see Tim Buckley perform at “La Cave,” then Cleveland’s sole performing venue for what we smugly termed “progressive” or “underground” pop music. Anxious to be seated close to the stage, we stood in a line on the stairs for two hours before the doors opened. We needn’t have--for it happened that we were the only ones who show up for the night’s performance. The La Cave manager, Stanley Kain, a hard-headed entrepreneur, promptly cancelled the performance and declined, as was his wont, to furnish any refunds. But he generously allowed us to stay as Buckley and his two-man band performed a brief rehearsal, the highlight of which was a languorously slow and hitherto unrecorded version of the Supremes’ hit, You Keep Me Hangin’ On. It made us feel special to be his select audience but the music ended all too quickly, and we quickly found ourselves back on the street with a tantalizingly brief memory and no remaining funds for any of Tim’s subsequent performances.We thought no more about it until late Saturday evening. Midnight, as usual that summer, found us high on reefers and desultorily wandering the streets of Cleveland Heights, specifically the grassy median strip of Euclid Heights Boulevard. There, unexpectedly, we met two musician friends, Walt Mendelssohn and David Budin, also at loose ends and seeking excitement. More interesting still was their companion, Tim Buckley, who had just finished performing at La Cave and now found himself tagging along with Walt and David, who had been jamming with him.

It was immediately obvious that Buckley was stoned out of his mind. He spoke little and haltingly—but the few words he uttered focused exclusively on two subjects: he wanted to get higher and he wanted to go swimming.

His first ambition was no problem. Retiring to our nearby back yard, we led him behind the garage into my father’s rose garden, stoked up a corncob pipe with marijuana and set to work in earnest.

We must have been back there a good half hour, huffing, puffing and holding it in to achieve maximum effect. And-oh yes--concentrating mightily on trying to BE COOL, because, after all, we were smoking grass with Tim Buckley. TIM BUCKLEY!!! ELEKTRA RECORDS RECORDING ARTIST TIM BUCKLEY! “The quintessence of nouvelle” Tim Buckley (as the album notes of his maiden release so fatuously gushed), “a study in fragile contrasts” with “sensitivity apparent in the very fineness of his features.” THAT Tim Buckley!—who at the moment was happily huffing and puffing along the likes of us suburban hippie poseurs!

My memory is that we scarcely said hardly a word, as we were petrified with fear that TIM BUCKLEY! would think us the doltish, uphip and uncool suburban teens that we were, alas, in fact. Eventually wearying of the pipe and, I suspect, our puerile company, Buckley reverted to his swimming quest. That, too, was hardly a problem but definitely involved more risk. As it happened, we had for some time that summer indulged in the nocturnal and illicit habit of sneaking into the outdoor pool at an apartment complex just two blocks away. Although fully illuminated at night, the pool area displayed no apparent security and we had slipped into a routine of going skinny dipping there when bored and high in the wee hours of the morning. So off we ventured, perhaps a half dozen of us, tripping and giggling through the sleeping streets of Cleveland Heights. Scaling the wooden wall around the pool perimeter, we shucked our clothing and plunged headlong and naked into the pool.

All might have gone well but for Tim Buckley. Maybe it was the drugs, maybe it was just his normal animal spirits finding release in the cooling medium. Or maybe it was his unspoken irritation with his nocturnal company. But the moment he hit the water he started squealing with delight, emitting sharp, small animal-like cries not unlike those found in his more improvisational vocal work. Inevitably, his quintessence of nouvelle squeals and, possibly, the not inconsiderable din of six or so adolescent boys splashing lustily aside him in the pool alerted an apartment security man, who suddenly appeared poolside, armed with a flashlight and demanding that we explain our presence there. Well . . . we might have been reckless, we may have been uncool and we were certainly at a loss for a snappy comeback. But we sure knew how to run from the police, which we forthwith did, grabbing our clothing and hauling ass, buck-naked and screaming over the wall. As we fled the scene, Buckley, David and Walt scurried in one direction and the rest of us in another. I can’t remember whether we halted to reclothe ourselves but I’m pretty sure we didn’t stop running until we arrived back at the rose garden.

And that was that. Although I continued to follow his music, I never saw Tim Buckley again, and I can recall thinking about him only twice in the years which followed our somewhat mortifying brush with celebrity. The first occasion was when he died in late June of 1975, seemingly just another celebrity casualty of the drug culture that had improbably united us behind my parents’ garage. (Fellow rock scholars may recall that Buckley succumbed to the effects of a massive dose of heroin.) The second was when his son Jeff drowned while swimming in 1997. I had never paid any attention to Jeff’s music, but I remember thinking how oddly ironic it was that my thoughts of the father and son should be linked by the notion of imprudent swimming. As I said to someone at the time, “I guess those Buckley boys just can’t keep away from the water.”

I still listen to Tim Buckley’s records, mostly, I suppose, just to remind me of a time when I was young and naïve enough to believe that getting wasted with a celebrity was as good as it got. Another irony, now that I come to think of it, is that Tim Buckley, who seemed a mature Rock God to me in my father’s garden, was but a year older than I at the time we met. Resquiat in pace.

Read the upcoming installment of Cleveland Confidential next week in CoolCleveland.com.

--***--

A Cautionary tale of the Sixties

by John Stark Bellamy II

Author’s note: Some of the names, most especially that of the central character of this narrative, have been altered, sometimes to protect the innocent and sometimes to shield the guilty.

My brothers and I flirted with catastrophe many times during the drug-drenched days of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Surely, however, we never came closer to disaster than the Joe Rupple Christmas imbroglio of 1967. At the time I was so shocked and scared I could scarcely believe the events that were occurring in front of me. But it did happen, and it came about in this wise.

I arrived home for Christmas from my first semester at St. John’s College on December 22. The following day my brother and I passed the tedious hours in the desultory but prolonged grass smoking that had become de rigeur for the last year on the third floor of the family manse. My mother had already informed us that my younger brother was bringing a guest, Joe Rupple, home for the holidays from the eastern college both attended, as Joe’s parents lived in Singapore and it would be inconvenient for him to fly back there simply for Christmas. So that evening my elder brother and I motored to the Greyhound Bus Terminal at East 13th Street and Chester Avenue to pick up my younger brother and Joe. Higher than kites but with unencumbered hearts, we were not prepared for what broke loose when we got there.

I arrived home for Christmas from my first semester at St. John’s College on December 22. The following day my brother and I passed the tedious hours in the desultory but prolonged grass smoking that had become de rigeur for the last year on the third floor of the family manse. My mother had already informed us that my younger brother was bringing a guest, Joe Rupple, home for the holidays from the eastern college both attended, as Joe’s parents lived in Singapore and it would be inconvenient for him to fly back there simply for Christmas. So that evening my elder brother and I motored to the Greyhound Bus Terminal at East 13th Street and Chester Avenue to pick up my younger brother and Joe. Higher than kites but with unencumbered hearts, we were not prepared for what broke loose when we got there.Joe and my younger brother were the first passengers off the bus, and the four of us huddled by its dirty side, waiting while the luggage was unloaded. I had noticed my younger brother looking nervous when he stepped off the bus, and I quickly discovered why. He had just endured eighteen hours on a Greyhound bus with Joe Rupple, and it was immediately obvious to me what he had known every second of that long journey: Joe Rupple was high—higher than just about anyone we had ever seen.

It wasn’t his dress or grooming that drew attention. Joe was handsome enough in a rangy way, and his full beard gave him an Old Testamenty gravitas that added several years to his actual age of 18. But it took only one look at his face to see that something was terribly wrong. His eyes, hugely dilated, gleamed back at you with the unmistakable shimmer of drug-fueled lunacy. But that wasn’t the worst part. Scarier still was his voice: an overpowering verbal Niagara of high-pitched, semi-hysterical and non-stop speed-freak words, words and more words.

What he was saying was alarming enough; what was worse was that he was saying it right OUT LOUD in a tone which could be heard a block away. Nor did he wait for a response to any of the words that poured from his mouth in an incessant flow: “YOU MUST BE THE BROTHERS! I’M JOE! ARE YOU STONED? DO YOU WANT TO GET STONED? LET’S GO TO THE LAVATORY AND GET HIGH? JOHN! JOHN! JOHN! LET’S GET HIGH IN THE LAVATORY! DO YOU HAVE THE HASH? IS THE PIPE STILL IN YOUR BOOT?! LET’S GET HIGH! LET’S GO TO YOUR HOUSE TO THE THIRD FLOOR AND GET REALLY, REALLY STONED!” Hoping to interrupt this incriminating monologue, I pushed him away from the bus and took him to the Men’s Room. That was a mistake. Seconds later, I dragged him out, just after he had invited a young black man attending a call of nature there to “smoke some dope with us soul brothers, dig, man?”

Grabbing the luggage, we finally managed to hustle Joe into the car and sped homeward. As the miles slipped by, Joe continued his non-stop monologue, alternately gushing at how glad he was to be with those hip Bellamy boys and petulantly demanding that we smoke some dope in the car.

Once we got home, things unexpectedly cooled down. Joe sat down to a late dinner with us and aside from some inappropriate boisterousness and embarrassing candor, managed to get through the meal without unduly alerting the suspicions of my parents. For one thing, whatever his behavior to the wary eye, he didn’t mention drugs and for another, my parents had already been prompted to make allowances for his behavior by his mother’s telephoned warning that he’d lived abroad for most of his life and was a relative stranger to American customs and behavior. As soon as the meal was finished, we hustled him to the third floor and smoked opiated hashish until we passed out.

Well, not quite all of us. When we woke up the next morning we discovered that Joe had not slept, nor had he been still. During their months together at college my younger brother had regaled him with tales of our adolescent mischief, and Joe had naively but indelibly incorporated elements of these anecdotes and their embedded personalities into his intense fantasy life. He was particularly fearful of a mythical figure known simply as “Scott” (a local high-school teacher notorious for smoking dope with his students), more positively keen to meet a legendary hipster known as “Slim” (a high-school chum of legendary muscularity and capacity for ingesting drugs) and childishly anxious to impress all he met with testimonials as to his personal sophistication and experience, particularly with reference to drug consumption. So while we had slept that night, he had methodically worked his way through the bookcases of my adjoining room, frantically scribbling such totemic words as “Scott,” “Slim” and his absolute favorite, “Reality” in my books and, when periodically inspired by thoughts of the impending holiday, “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Bag!” He had also, although this did not become apparent for some days, purloined Christmas ornaments from the first floor Christmas tree and concealed them in various unexpected places, mostly under chair cushions and at the back of bookcases.

Breakfast on Christmas Eve morn was a nightmare. Joe babbled incessantly and repetitively as we ate, and I could see my mother showing the first signs of real concern, the corners of her mouth drawing tighter and tighter as the dimensions of his mania progressed. Indeed, the mood at the table became so uncomfortable that we were relieved when Joe abruptly arose from his seat and disappeared.

The winter afternoon hours slipped by with no sign of Joe. It being Christmas Eve, my parents had prepared their annual holiday dinner, an elaborate entertainment to which they inflexibly invited several dozen of their oldest and dearest friends. Five o’clock came, darkness descended and the first guests began straggling in—and still no sign of Joe. By 6 pm the party was in full swing, the alcohol was briskly flowering and still no sign of Joe. Uninterested in the party, my brothers retreated to the third floor lair for some serious hashish consumption, leaving me to greet the guests as they arrived at the front door and subsequently assuring that they were well supplied with glasses of champagne.

I knew something was amiss when the door bell rang, and I opened the front door to find no one there. This likely meant there was someone at the back door, so I walked there, opened the door . . . and found myself looking at an unexpected threesome: a terrified Joe Rupple in the obvious custody of two burly Cleveland Heights policemen.

The story as best the policemen could reconstruct it went like this. After leaving the house that morning, Joe had eventually wandered into nearby Lake View Cemetery, about which he had likewise heard many intriguing tales from my younger brother. He’d spent the afternoon walking around the cemetery and, he later claimed, actually encountered my uncle’s gravestone, an unsettling event, as it was graven with my name: JOHN STARK BELLAMY. Eventually, he wandered out of the cemetery, lost and disoriented, and began walking down Mayfield Road. We’ll never know what was going on in his chemically addled head, but whatever it was moved him to cross the street and start knocking on the doors of the homes there. Then, as soon as someone answered the door, he would scream maniacally, “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Bag!” and run away. Eventually, someone called the police, they picked him up, and he had just enough brain cells left to tell them with whom he was staying.

It could have been much worse. The two cops probably—hell, certainly knew Joe was higher than a kite, and they could easily have made things highly unpleasant for both him and us. But, thanks to my father’s prominent position as a journalist and the known fact that we were well acquainted with our back-fence neighbor—the Police Chief of Cleveland Heights—they decided to handle the matter with, ah, considerate discretion. I was soon joined in this back door colloquy by my father, to whom they explained that Joe had been acting in an irrational manner and had frightened some residents, and they were more than happy to relinquish Joe to my father’s custody and leave the matter to his discretion.

I don’t know what we should have done. I can only be sure about what we did, which was to hustle Joe back up to the third floor and ply him with more narcotics, in the hope that that enough narcotics would conk him out and, perhaps with the aid of a good night’s sleep, calm him down at last.

It didn’t work. The first thing that struck me as I struggled awake the next morning was that Joe was already up and bustling around the third floor. Indeed, when I reached full consciousness I realized he had already busied himself by disassembling the flushing mechanism of the toilet tank and was now attempting to reconstruct it as a serviceable hash pipe, an obscure craft that he and my brother had learned at college. But I barely noticed this minor incident and the disagreeable misfortune that we now lacked a working third-floor toilet—for I was immediately distracted by the fact that Joe Rupple was talking faster than anyone I had ever heard in my life. Sure, I’d experimented with some amphetamine pills and the acid we frequently dropped was heavily laced with the stuff—but Joe’s current logorrhea was clearly pathological and downright scary. We all took turns trying to talk him down but with little success, so we decided we had to get him out of the house before his symptoms became obvious even to non-drug users like my parents.

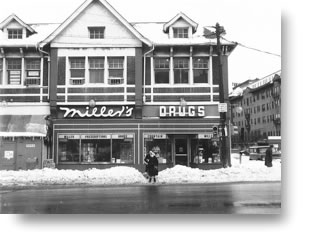

My recollection is that we walked two blocks over to Miller’s Drug Store at Cedar-Fairmount and sat at the counter for an hour, drinking cherry cokes and eating order upon order of heavily buttered toast. The food and the outdoor air seemed to have the hoped for sedative effect on Joe—that is, until we got home. The moment we came through the back door he started running up the stairs to the third floor. Hot on his heels, we followed.

My recollection is that we walked two blocks over to Miller’s Drug Store at Cedar-Fairmount and sat at the counter for an hour, drinking cherry cokes and eating order upon order of heavily buttered toast. The food and the outdoor air seemed to have the hoped for sedative effect on Joe—that is, until we got home. The moment we came through the back door he started running up the stairs to the third floor. Hot on his heels, we followed.We needn’t have hurried, for there was no sign of Joe when we got to the third floor. But a minute later my mother shouted up the stairs that Joe was standing outside her window—on the second floor roof of the house. We ran down to her bedroom and, sure enough, there was Joe, gesticulating wildly and shouting from the other side of the window. There was only one explanation, and it was evident even to my mother: he had crawled out the third floor window at the front of the house and leaped down to the second floor roof.

Matters degenerated rapidly after that. By now it was impossible to conceal his condition from anyone. Ceaselessly pacing, Joe couldn’t stop talking, and his speech was a high-pitched, unstoppable monologue of catch phrases and repetitive slang welling up from his addled brain. “Fish? Reality! Slim?” and constant references to the feared “Scott!” Not to mention his repeated admonitions to “Have a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Bag!”

My mother may have been naïve about drugs, and she had long since become used to young men outrageously acting out in her presence. But she wasn’t an idiot, and it was obvious that Joe had reached the point where he was dangerous to himself and possibly others. So she contacted the only mental health professional she knew, the husband of my father’s first-cousin, a psychologist whom, for purpose of this memoir we shall call “Dr. Scabman.”

An hour or so later, Dr. Scabman got to the house. To say the least, both his odd appearance and disquieting manner only increased Joe’s agitation and paranoia. Repeatedly shouting at him, “Are you Scott? You’re Scott—aren’t you?” Joe refused to answer the doctor’s queries about his condition and waxed wilder and more menacing by the minute. Fortunately, at this juncture, our friend Wilbur arrived.

Like most of our friends in that era, Wilbur was a little, well, eccentric. For example, he was one of the few teenagers I knew who wrote properly scanning sonnets. Bohemian almost to a fault—a category in which he had much peer competition--Wilbur boasted an interest in the farther reaches of English literature, charmingly affected manners, a taste for the occult and dandyish dress. In other words, he was just the weirdly calming and slightly bizarre influence needed under the circumstances. Impressed by his unusual manner and fanciful dress, Joe soon concluded that Wilbur was a magician with great powers and special knowledge. While they chatted, Dr. Scabman consulted with my mother. To say the least she was in a difficult position. With Joe’s parents in Singapore, happily ignorant of his dire condition, she was in loco parentis, confronted with a novel situation and unsure what to do. But finally, after some consultation with my father by telephone, it was decided to take Joe down to Hanna Pavilion (the psychiatric component of University Hospitals) for diagnosis and possible hospitalization. With Wilbur by now astutely playing the role of his magical mentor and spiritual director, Joe was eventually coaxed into an automobile and I accompanied him, Wilbur, my mother and Dr. Scabman to Hanna Pavilion.

There, the nightmare continued. Directed to the 4th floor, we soon found ourselves uneasily ensconced with Joe in a locked ward—with at least a dozen other mental patients, some staff and what I recall was a policeman standing guard. Things got off to a shaky start with Joe turning to me, and in the presence of the guard, asking, “John, why don’t you get that hash and pipe out of your boot and we’ll toke up with this fine policeman?” Notwithstanding the fact that I did have half an ounce of hashish on my person—with events breaking fast and furious it hadn’t seemed safe to leave it anywhere in the house—I coolly replied that I was furnished with no such materials and that his hope was vain. Every few minutes Joe would be shuttled out of the room by doctors for further examination, then returned, while we waited and the hours slipped by. At last, I think it was about 5 p.m.—perhaps five hours after this crisis had developed—word finally came that Joe could not be admitted to Hanna Pavilion. So once again, Wilbur and I bundled him into the car and our strange entourage motored a few blocks over to Mt. Sinai Hospital on East 105th Street. Whisked quietly upstairs to the psych ward, Joe was quickly signed in and left the room in the custody of two men in the proverbial white coats. Somberly, my mother, Dr. Scabman, Wilbur and I began walking to the elevator. But just as the doors opened, we heard a terrible scream behind us and wheeled around to see Joe running towards us, screaming “Don’t leave me! Don’t leave me! Don’t leave me!” as a phalanx of white-coated men chased after him. Catching him as he cowered before us, they pinioned his arms and dragged him away, screaming and fighting every painful, anguished step of the way.

The incidents of the subsequent two months lacked the exciting drama of Joe’s early days but provided plenty of prolonged and unpleasant tension. A week after Joe’s incarceration, his mother arrived to take up temporary residence at my parents’ home while she dealt with her hospitalized son. She was not, to say the least, in a good mood, notwithstanding her gratitude to my mother for her initial handling of a difficult situation. Utterly convinced of her son’s rectitude, she refused to believe that his previous over-experimentation with drugs, well attested to later by various college acquaintances, had inevitably led him to the chemically-induced psychosis that now possessed him. (Even my younger brother didn’t know the genesis of his breakdown—he only knew that Joe had gone to Boston with several hundred dollars and returned from there in a drug-demented state, just hours before his projected jaunt to Cleveland.) Unable to learn exactly what had triggered his descent into madness—the only coherent clue she wrung out of Joe was the feeble admission that he might have taken a solitary “pep pill” to help him study for his semester finals—his mother began selecting scapegoats for her son’s pathetic condition.

She didn’t have far to look and her residence at the Bellamy house made her quest all too easy. Immediately and instinctively focusing on my younger brother—who returned her disdain with relish—she made it her mission to discover and expose, if possible, my brother and the rest of us in possession or use of the kind of drugs she suspected had caused the disintegration of her son’s mind. Restlessly stalking the corridors and rooms of the house, she would suddenly pounce upon us, peering into our ranks and ransacking our rooms in hopes of espying a telltale corncob pipe, a plastic marijuana baggie or an incriminating chuck of hashish. She never succeeded in her researches but there were several close calls—we weren’t about to stop using drugs daily just because of some nosy parent—and it was nerve-wracking having our own personal Javert lurking about at all times and in unexpected places. But in early January my younger brother escaped her scrutiny by going off to New York City to fulfill his off-campus commitment and I departed soon after, returning to Annapolis for my second semester at St. John’s College. Mrs. Rupple remained at my mother’s house for several months more, finally returning with Joe to Singapore in the late spring of 1968.

That was pretty much the end of the Joe Rupple episode. As a token of her gratitude, Mrs. Rupple purchased a badly needed dryer for my mother’s basement and she kept in touch by Christmas card for some years after that. Joe never returned to my brother’s college and the last I heard of him was that, after years of drug abuse and repeated personal crises that nearly bankrupted his parents, he had eventually settled down to some success as a professional chef in New Orleans. I don’t know whether that is so but I do now that he made Christmas 1967 a Yuletide to remember.

Read the upcoming installment of Cleveland Confidential next week in CoolCleveland.com.

Read earlier episodes of Cleveland Confidential here.

--***--

Photo credits: 1) Greyhound Bus Terminal; 2) Heights Center Building, 12429 Cedar Road on 2/11/71. Includes Miller's drug store. Alcazar Hotel can be seen on the far right. Photo courtesy of Cleveland Heights Historical Center.

The Circle Game: A Cleveland Memoir

Part 2

by John Stark Bellamy II

Having effectively neutralized the Coffeehouse as a gathering place for the drug-inclined, Cleveland Police turned their wrath on Stanley Heilbrun’s Headquarters. It took them a little longer but the results were both more dramatic and decisive. On April 20, 1967, Cleveland Police narcotics squad officers raided Heilbrun’s home at 11312 Hessler Rd. Seizing marijuana and drug paraphernalia, they arrested Heilbrun and charged him with possession.

More ominously, he was also charged with two counts of providing drugs to a minor, a 16-year-old girl. Facing a possible 62-year prison stint, Stanley jumped bail in early January, 1968, just days before his scheduled trial before Judge John T. Patton. He left behind a tendentious but oddly eloquent letter, which the Cleveland Press, to its credit, saw fit to publish. It read in part:

The narcotics charges against me are thinly disguised maneuvers to

close my book store. I am not guilty of those charges; that is not why

I’m running. I had naively believed that our constitutional guarantees

were specifically framed to protect those with controversial ideas.

The artist, intellectuals, hippies and students in general have been

suffering outrage after outrage from the police. We have been crying

out pain but to deaf ears. Those reporters who have been aware of

what has been going on have been unable to print their observations

because of reactionary, police-controlled editors. Instead those

elements of society who are most committed and concerned are made

the public scapegoats for conservative reaction against the many

frustrations of social change which are so confusing to all of us. I am

certain that you, the hard-working respectable people of Cleveland

cannot accept my claim that a police state is being thrust upon us; you

do not feel its effects. You regard us as criminals, traitors and trouble-

makers who deserve the wrath of the law. But when they begin

silencing the books, the ideas, the treacherous road to fascism is being

well-paved. If we are screwballs, it is because our warnings to you are

met with police clubs. You do not believe us when we say your news-

papers are controlled, your leaders lie. As you continue to confront

1968 with 1940 attitudes, you will be led deeper into insanity abroad

and war at home. You in Lakewood and Shaker will begin to feel the

weight of the ignorant, authoritarian bureaucrats we have. I regret

deeply that I cannot stay here and help. It is not just Russia and

Greece from which free men must flee for their lives. As I have

already suffered great injustice at the hands of the sacrosanct public

officials, I hardly expect better in the courtroom. As you continue to

see your children arrest for smoking marijuana and having long hair,

perhaps my flight will begin to have meaning to a few of you. Just as

Germany began with Gypsies, then Jews, so the United States has its

hippies and Negroes. I hope that I can find a nice quiet river bank

somewhere where I can write my music in peace.

Adele’s proved a harder nut for the powers-that-be to crack. Owner Prengler possessed both an extended lease on the property and a combative temperament to match the ire of his antagonists in the Cleveland Police Narcotics Squad and the University Circle Development Foundation. Even as the systemic throttling of the Coffeehouse and Headquarters intensified, he waged canny legal combat with his adversaries and frequently vented his complaints to obliging reporters.

In November of 1967 he talked to the Cleveland Press hippie expert, Dick Feagler (who that May had actually met Janis Joplin backstage at a Big Brother & the Holding Company San Francisco concert and failed to identify her in his story about the encounter) about official exertions to cancel his liquor license:

In November of 1967 he talked to the Cleveland Press hippie expert, Dick Feagler (who that May had actually met Janis Joplin backstage at a Big Brother & the Holding Company San Francisco concert and failed to identify her in his story about the encounter) about official exertions to cancel his liquor license: They wanna’ get me out of here. But I got a four-year lease. So

they try to take my license. They turn off my jukebox. They come

with flashlights and inspect my sanitation. They say my customers

stink. Look around. Do you see customers that stink? Why, professors

come in here. Some of them wear beards. I’m supposed to say, go

home, shave, then I’ll serve you. It’s against the law. They say

motorcycles come here. Is there a law against motorcycles? Never

once was a stabbing and shooting inside my place. People call. They

say, what time can we see the hippies? I say, come by at eight o’clock.

I keep them in the basement. What kind of foolishness is this?

Ginsberg comes to town. There is a fight in the parking lot behind my

place. They blame me. Am I supposed to follow Ginsberg all over

town? Nonsense.

The campaign to close down Adele’s would continue for several more years, and the bar would ultimately succumb, the victim of police hostility, yet another suspicious fire and the planning ambitions of the University Circle Development Foundation. Ironically, though, the war against the Circle drug culture had already been utterly lost.

During the spring of 1967 I had listened one evening in the Headquarters as Stanley Heilbrun prophesied, with his usual apostolic fervor, that the next commercial hippie enclave would arise on Coventry Road in Cleveland Heights. (For the record, I thought his prediction was “crazy,” and said so. “Coventry Road? A down-at-the heels retail area of small merchants with a predominately Jewish ambiance? You’ve got to be kidding, Stanley!”)

By the spring of 1968 Heilbrun’s prophecy was already coming true, a reality subsequently certified by the first serious police drug raids there the following September. An additional irony that Heilbrun might have relished was that the Adele’s-centered biker scene—increasingly violent and ever more involved in high-end criminal drug activity—also gravitated from the beleaguered tavern to a Coventry Road bar. (During the summer of ’69, Cleveland Heights Police Chief Edward Gaffney would wage an ultimately successful war to drive the bikers out.)

By that time there was little left of the Circle hippie haven, save a few hangers-on who hadn’t gotten the message or could stomach the increasingly hostile demeanor of the biker habitués at Adele’s. Another nail in the coffin of the Circle drug scene occurred in May, 1968, when Stanley Kain, the chief figure at La Cave, a crucial performance venue for musicians beloved by the drug community, was arrested—and subsequently convicted for conspiring to sell massive quantities of LSD.

My last personal memory of the Circle is a rainy summer night in 1968. Home from college and unaware of the sea change in the Cleveland counterculture, I walked down to East 115th in hopes of finding my wonted hallucigens. Arriving there, I found the Coffeehouse shuttered and but a few customers in the Graffiti bookstore. To complete the gloomy scene, rain was pouring down, but there was a reassuringly familiar figure standing in front of the latter, a longtime drug purveyor who happened to be the son of a prominent suburban police chief. (He was subsequently busted for said activity, but that’s another story.)

Apprised of my urgent need, he sardonically muttered, “Oh, yes, here’s something for your headache,” and reaching into his pocket, pulled out a small bottle of white pills and began pouring them into my eager hands. Unfortunately, we were both shaking (he from the effects of drugs, I from fear of being observed breaking the law), and all of his precious white pills fell scattering to the sidewalk below. So my last memory of the Circle drug scene is an unglamorous one of scrambling on my hands and knees on the wet Euclid Avenue sidewalk, frantically picking up tiny white pills and hoping I wouldn’t live to regret it.

I can still remember turning to my companion, as we hurried homeward up Mayfield Road to safe haven in the Heights, and saying, “I don’t think I’m ever going to do this again.” And every word of my story is true, except that some names, save my own, have been changed to protect the guilty.

--***--

Read the upcoming installment of Cleveland Confidential next week in CoolCleveland.com.

Read earlier episodes of Cleveland Confidential below.

Photo credits: 1) "[Cleveland Press reporter Dick] Feagler at pot party with hippies," 4/26/67, courtesy Cleveland Press collection, Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University; 2) Also of interest: Rare film footage [please click picture at left] of d.a. levy reading his poetry at The Case Institute of Technology Strosacker Auditorium, May 14th, 1967. The event was organized in effort to raise funds to help levy and Cleveland bookseller Jim Lowell's legal defense after the two were charged with reading and distributing "obscene" literature at poetry readings and at Lowell's Asphodel bookstore in Cleveland.

Photo credits: 1) "[Cleveland Press reporter Dick] Feagler at pot party with hippies," 4/26/67, courtesy Cleveland Press collection, Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University; 2) Also of interest: Rare film footage [please click picture at left] of d.a. levy reading his poetry at The Case Institute of Technology Strosacker Auditorium, May 14th, 1967. The event was organized in effort to raise funds to help levy and Cleveland bookseller Jim Lowell's legal defense after the two were charged with reading and distributing "obscene" literature at poetry readings and at Lowell's Asphodel bookstore in Cleveland.

Former Clevelander John Stark Bellamy II is most notorious for his books chronicling Cleveland murders and disasters, such titles as They Died Crawling, The Maniac in the Bushes and Women Behaving Badly. Countryman Press has also published an anthology of his Vermont murder tales, Vintage Vermont Villainies. This CoolCleveland.com exclusive is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progess, Wasted on the Young.

Former Clevelander John Stark Bellamy II is most notorious for his books chronicling Cleveland murders and disasters, such titles as They Died Crawling, The Maniac in the Bushes and Women Behaving Badly. Countryman Press has also published an anthology of his Vermont murder tales, Vintage Vermont Villainies. This CoolCleveland.com exclusive is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progess, Wasted on the Young.This fall Gray & Co. will publish a compilation of his disaster stories, including narratives of the Cleveland Clinic gas tragedy, the East Ohio Gas Co. explosion, the 1916 waterworks tunnel blast and a dozen more defining Cleveland castrophes.

Although he keeps a fond and constant eye on all things Cleveland cool and otherwise, John now lives with his wife Laura and their dog Clio in the most soothing part of Vermont, where he continues to recuperate from the excitements and follies of his excessively prolonged youth.

The Circle Game: A Cleveland Memoir

Part 1

by John Stark Bellamy II

It’s no secret that Cleveland forsakes its past. Forest City journalist George Condon once wrote that no major city in the United States has a more deplorable record than Cleveland when it comes to venerating and preserving its historic sites. I couldn’t agree more--and I’m not alluding to the dismantlement of its industrial landscape or the eclipse of its fabled “Millionaires’ Row” mansions. Those are largely past physical recall but at least have been perpetuated, after a fashion, in various publications and archival institutions. No, I refer to scenes of the more recent, if somewhat raffish past. It’s a regrettable fact that there are no historical markers at the corner of East 115th Street and Euclid Avenue. And that’s a shame, because that intersection played a memorable role in the genesis of Cleveland’s first counterculture: the “hippie” drug scene of the mid-1960s.

It’s no secret that Cleveland forsakes its past. Forest City journalist George Condon once wrote that no major city in the United States has a more deplorable record than Cleveland when it comes to venerating and preserving its historic sites. I couldn’t agree more--and I’m not alluding to the dismantlement of its industrial landscape or the eclipse of its fabled “Millionaires’ Row” mansions. Those are largely past physical recall but at least have been perpetuated, after a fashion, in various publications and archival institutions. No, I refer to scenes of the more recent, if somewhat raffish past. It’s a regrettable fact that there are no historical markers at the corner of East 115th Street and Euclid Avenue. And that’s a shame, because that intersection played a memorable role in the genesis of Cleveland’s first counterculture: the “hippie” drug scene of the mid-1960s.Had you been an eagle soaring high above University Circle of an early winter’s night four decades ago, you might have observed a remarkable phenomenon. For from that lofty station you could have espied clusters of young Clevelanders, both city dwellers and suburbanites, stealthily converging on the hitherto shabby and unsought corner of East 115th and Euclid Avenue. By ones and twos, by foot and by automobile, from every quarter of the compass they trekked there as to a Holy Grail. Why? Because it was December 1966 and this unlikely intersection had become the fast beating heart of the Cleveland counterculture. Central to that culture was the unifying sacrament of illegal drug use, and it was already notorious that this juncture of “The Circle” was the chief portal to criminally chemical redemption.

Looking back, the modest locale of our youthful drug Mecca seems even more improbable and unprepossessing than it then did. Composed of just three elements, not a single one suggested its historic role in undermining the morals and character of Cleveland’s young. First was the Coffeehouse, situated on the northeast corner. Previously but a disheveled storefront, it blossomed, under the stewardship of 24-year-old ex-Western Reserve University zoology student Wade Ferrel, into a major hippie hangout by the fall of ’66. True, it was generally unheated, damp and drafty, as if someone had left a window open for a timely escape from the police. Dimly lit, it offered only a Spartan menu of mediocre coffees and other non-alcoholic beverages. (The most notorious of these leprous distilments was the “Psychocoke,” an odious blend of Coca-Cola and cider which Ferrel himself pronounced “not very good.”1) Nor was music the principal charm of the Coffeehouse ambiance, though its jukebox boasted offerings beyond the Top 40 ghetto (one fondly recalls “Scotch and Soda” by the Kingston Trio, Tim Hardin’s “The Lady Came From Baltimore” and—of course—“Mother’s Little Helper” by the Stones) and an attractively out-of-tune and battered piano huddling against the front wall.

Looking back, the modest locale of our youthful drug Mecca seems even more improbable and unprepossessing than it then did. Composed of just three elements, not a single one suggested its historic role in undermining the morals and character of Cleveland’s young. First was the Coffeehouse, situated on the northeast corner. Previously but a disheveled storefront, it blossomed, under the stewardship of 24-year-old ex-Western Reserve University zoology student Wade Ferrel, into a major hippie hangout by the fall of ’66. True, it was generally unheated, damp and drafty, as if someone had left a window open for a timely escape from the police. Dimly lit, it offered only a Spartan menu of mediocre coffees and other non-alcoholic beverages. (The most notorious of these leprous distilments was the “Psychocoke,” an odious blend of Coca-Cola and cider which Ferrel himself pronounced “not very good.”1) Nor was music the principal charm of the Coffeehouse ambiance, though its jukebox boasted offerings beyond the Top 40 ghetto (one fondly recalls “Scotch and Soda” by the Kingston Trio, Tim Hardin’s “The Lady Came From Baltimore” and—of course—“Mother’s Little Helper” by the Stones) and an attractively out-of-tune and battered piano huddling against the front wall.Say what you will about the actual purpose and function of the Coffeehouse—and Cleveland Police officials and University Circle Development Foundation personnel said plenty—Wade Ferrel and its subsequent proprietors consistently insisted that it was simply a modest, inexpensive venue where students and other young people with no taste for alcohol could socialize. And Ferrel was probably stating the technical truth when he protested the druggy image of his establishment relentlessly promoted by local law enforcement officials and frequently echoed in the columns of Cleveland newspapers:

They don’t all want to go to bars, you know. . . . People have the

impression that a lot of mainliners hang around here. It simply isn’t

true. I don’t know of single drug addict who comes in the

Coffeehouse. Students come in here to talk and socialize. Our

entertainment is spontaneous. Maybe somebody brings a guitar and

then everybody sings folksongs. We tried poetry readings but

nobody listened.

Two doors east of the Coffeehouse came the second vital element in Cleveland countercultural nexus, Stanley D. Heilbrun’s Headquarters. Known to most of its habitués simply as “the Head shop,” Heilbrun’s ramshackle and cluttered emporium featured the usual array of countercultural consumer goods, including lavish drug accoutrements (hash pipes, hookahs and Zig-Zag cigarette papers), posters (Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Jimi Hendrix and the other usual suspects), overpriced “thrift” garments and seductive novelties like penny Tootsie Rolls and miniature busts of Adolf Hitler carved from coconuts. And not for Stanley H. were the blushing disclaimers of a Wade Ferrel. No, indeed: Heilbrun was a self-styled chemical evangelist who minced no words about his sacred mission. Unabashedly promoting his store to delighted newspaper reporters as a “propaganda center for psychedelic drugs,” 2 Heilbrun pridefully boasted that every item for sale there was either “satiric, esoteric or acid-teric.” 3

Two doors east of the Coffeehouse came the second vital element in Cleveland countercultural nexus, Stanley D. Heilbrun’s Headquarters. Known to most of its habitués simply as “the Head shop,” Heilbrun’s ramshackle and cluttered emporium featured the usual array of countercultural consumer goods, including lavish drug accoutrements (hash pipes, hookahs and Zig-Zag cigarette papers), posters (Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Jimi Hendrix and the other usual suspects), overpriced “thrift” garments and seductive novelties like penny Tootsie Rolls and miniature busts of Adolf Hitler carved from coconuts. And not for Stanley H. were the blushing disclaimers of a Wade Ferrel. No, indeed: Heilbrun was a self-styled chemical evangelist who minced no words about his sacred mission. Unabashedly promoting his store to delighted newspaper reporters as a “propaganda center for psychedelic drugs,” 2 Heilbrun pridefully boasted that every item for sale there was either “satiric, esoteric or acid-teric.” 3Then there was Adele’s Lounge Bar, the last and perhaps most improbable unit of the block’s bohemian triad. Well predating both the Coffeehouse and Headquarters, Adele’s was then managed by feisty part-owner Martin Prengler, and his tavern was already undergoing its uncomfortable but inexorable transition from a funky neighborhood watering hole to a volatile nexus between Cleveland’s hippie and biker subcultures. For whatever their obvious differences, the shared preferences of the two groups for unconventional lifestyles and illegal chemical delights inevitably pushed them together, and Adele’s, whatever Prengler’s intentions, served as the necessary human interface. And, for the record, Prengler’s stance of outraged and injured innocence eclipsed even Wade Farrel’s arsenal of pious denials. Commenting on police charges that his bar was a center of drug activity, he fulminated to a Cleveland Press reporter:

Those kids are lying about what is going on here. There are no

narcotics here. I can’t control other places in the area. We run a nice,

respectable place. This place is definitely not a nuisance. All this

publicity has cut our business in half. You can’t chase customers out

just because they have long hair and beards. I’m not their mother or

father.

One still particularly recalls with a shudder one’s first encounter at Adele’s with the phenomenon of “biker” women with their painfully tight clothes, heavy makeup, hard faces, all of them invariably introduced as “my old lady.”

Such was the setting of our youthful drug follies as the fall of 1966 lurched towards winter. Every Friday and Saturday and many a weekday night we trudged to our fateful corner in anxious hope of “scoring” some “grass” or “hash”—the fabled glories of LSD, or “acid,” not having yet penetrated our high school milieu. Our procurement routine was simple and quite as rigid as a pre-Vatican II Tridentine Mass. Sauntering through the door of the Coffeehouse, we’d order something cheap to drink, convinced, like true drug sophisticates, that such a prop would cunningly mask our true purpose on the premises. Now, with more elaborate casualness, it was over to the juke box, where we self-consciously selected tunes that wouldn’t shame our hipness quotient in the hearing of any college students present.

Then we would sit, and sit and maybe sit some more, sullenly waiting for some acknowledged candy man to come through the door. Usually that blessed event would eventually occur, and after a whispered exchange and the furtive transfer of folding money from hand to sweating hand—transactions doubtlessly obvious to denizens of the planet Mars—our vendor would depart. More waiting, more sitting, more paranoia ensuing as the minutes crawled by with no sign of our seller or his precious cargo. Finally, almost without exception—as Bob Dylan noted at the time, “To live outside the law, you must be honest”--he would reappear at the entrance.

Even as the door opened, we were on our feet striding towards him, and as we passed each other in the open street door, we palmed the packet of drugs and were on out way out of the Circle, up to the Heights, up to our third-floor room and back into the magic realm of being stoned. And on those rare occasions that we failed to score, there was at least the consolation prize of a visit to Dean’s Diner, just across Euclid Avenue, where the staff was not over-scrupulous about selling their gigantic jugs of 3.2 beer to blatantly underage males.

Our second fallback option was the package store at the Commodore Hotel, where they would sell bottles of Colt .45 (“Colt .45 is not a beer—It is a completely unique experience in drinking pleasure!”) and Orange Flip (a disgusting but emphatically effective admixture of vodka and orange juice) to anyone who could reach the store counter. On one occasion I actually witnessed the sale of this potent liquid combo to a twelve-year-old boy, whose head barely reached the top of the retail counter.

What a scruffy, tatterdemalion lot we were! Rigidly conformist in our teenage non-conformity, the boys uniformly sported Beatle haircuts, Cuban-heeled “Beatle boots,” blue Levis and black pea coats, the collars turned up against the cutting Circle winds. Those with hats generally chose pork pie, poor-boy styles, with the more stylishly affluent opting for the model memorably worn by John Lennon in the movie Help! Our girls, already stigmatized with the sobriquet of “hippie chicks,” (Women’s Liberation was yet but a gleam in some angry eyes), usually wore flowing Indian print frocks, with flowers in their long Joan Baez-style hair and eye-popping hats. All the boys smoked Marlboros compulsively and many of us, alas, even attempted something of a public strut.

A few melodramatic scenes emerge from the fog of memory: The progressively desolate look of the Circle area, a broken lunar landscape of crumbling apartment buildings, deteriorating commercial blocks and the debris-strewn vacant lots which seemed to multiply by the month . . . A beautiful, terrified suburban girl of 15, brought to my Coffeehouse table by her friends to be talked down out of the terror of her first LSD trip . . . a half-dozen police cars, top lights blazing, suddenly screaming to a halt and their occupants erupting into the street to seize and search everyone in sight . . . the sudden dry feeling in my mouth as the cops grabbed the persons sitting right next to me in the Coffeehouse and took them outside and a little voice inside me screamed “Please don’t search me!”

Obviously, our clumsy routine of drug acquisition was not built to last. As should be clear from the above, we were a little less than shrewd pr smooth in the protocols and etiquette of our delinquencies—and Cleveland area cops were hardly as dumb as we presumed in our youthful ignorance. By the autumn of 1966 they were angrily aware of the burgeoning drug scene, both in its University Circle incarnation and its spreading cells metastasizing throughout Greater Cleveland suburbs.

After some months of observation and infiltration, the first busts went down on December 7, 1966, when Cleveland Heights police arrested a handful of student drug users and several of their adult suppliers. The gravity of this crackdown was clearly underscored by Cleveland Heights Police Captain Earl Gordon, who, in announcing the busts, solemnly emphasized that the arrested students had “come from good homes and their parents are mostly professional people.”5 More arrests followed over the next week, spreading quickly to Shaker Heights High School, and publicized with banner headlines in the afternoon Cleveland Press, whose editor Louis Seltzer, always keen to sniff out the latest social menace, knew he had a hot one this time. And, surely, this story had legs that wouldn’t quit:

After some months of observation and infiltration, the first busts went down on December 7, 1966, when Cleveland Heights police arrested a handful of student drug users and several of their adult suppliers. The gravity of this crackdown was clearly underscored by Cleveland Heights Police Captain Earl Gordon, who, in announcing the busts, solemnly emphasized that the arrested students had “come from good homes and their parents are mostly professional people.”5 More arrests followed over the next week, spreading quickly to Shaker Heights High School, and publicized with banner headlines in the afternoon Cleveland Press, whose editor Louis Seltzer, always keen to sniff out the latest social menace, knew he had a hot one this time. And, surely, this story had legs that wouldn’t quit:POLICE SMASH NARCOTICS RING INVOLVING HEIGHTS HIGH STUDENTS (Cleveland Press headline, December 8)

MORE TO BE INDICTED IN SCHOOL DRUG CASE (Cleveland Press headline, December 9)

POLICE SAY DRUGS MADE ON EUCLID (Cleveland Press headline, December 13)

DOPE PROBE HITS STUDENTS OF 2 SUBURBAN SCHOOLS (Cleveland Press headline, December 14)

And—I think I said the cops were not dumb—inevitably:

TAVERN ON EUCLID AVE. LISTED IN DRUG PROBE (Cleveland Press headline, December 15)

ASK POLICE TO CLOSE HANGOUTS ON CIRCLE (Cleveland Press headline, December 16)

With suburban kids from good families now officially at risk, it was certain that stern retribution would follow, and it came swiftly. Citing “health and safety” violations that had hitherto eluded them, Cleveland Police officials forced the Coffeehouse to close down on December 20. After correcting the stated violations Wade Ferrel managed to reopen it, only to have it immediately reshuttered when Cleveland Police Lieutenant Sirkot conveniently discovered a padlock on an electrical switchbox. The pattern of police harassment continued for the duration, including an April, 1967 closing triggered by an unlicensed jukebox. (That technical breakage of the law was helpfully provided by a Cleveland policeman who obligingly dropped a dime in the music machine to establish the legal pretext.)

Two months later Ferrel threw in the towel but the Coffeehouse retained its fitful existence under manager Cleo Malone until the spring of 1968. But it was never the same after the initial closing, and the end came on March 12, when a fire of highly suspicious origin gutted the building housing both the Coffeehouse and the Graffiti Bookstore, the cultural successor to the Headquarters. It was symptomatic of the increasing paranoia of the time that rumor immediately suggested that Cleveland authorities had suborned some of their stoolies in the area to kindle the blaze...

--***--

Photo credits: 1) John Stark Bellamy II (before), courtesy of John Stark Bellamy II; 2) *The Coffee House and Adele's Bar & Lounge at E. 115th & Euclid 3) John Stark Bellamy II (after), courtesy John Stark Bellamy II; 3) *Police action on Coventry Road, 8/4/69. Photos marked * are courtesy Cleveland Press collection, Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.

Former Clevelander John Stark Bellamy II is most notorious for his books chronicling Cleveland murders and disasters, such titles as They Died Crawling, The Maniac in the Bushes and Women Behaving Badly. Countryman Press has also published an anthology of his Vermont murder tales, Vintage Vermont Villainies. This CoolCleveland.com exclusive is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progess, Wasted on the Young.

Former Clevelander John Stark Bellamy II is most notorious for his books chronicling Cleveland murders and disasters, such titles as They Died Crawling, The Maniac in the Bushes and Women Behaving Badly. Countryman Press has also published an anthology of his Vermont murder tales, Vintage Vermont Villainies. This CoolCleveland.com exclusive is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progess, Wasted on the Young.This fall Gray & Co. will publish a compilation of his disaster stories, including narratives of the Cleveland Clinic gas tragedy, the East Ohio Gas Co. explosion, the 1916 waterworks tunnel blast and a dozen more defining Cleveland castrophes.

Although he keeps a fond and constant eye on all things Cleveland cool and otherwise, John now lives with his wife Laura and their dog Clio in the most soothing part of Vermont, where he continues to recuperate from the excitements and follies of his excessively prolonged youth.